The Anthropology of the Image

In the information-heavy world of today, the impact of the image is vastly overlooked by both the masses and society’s designated experts. The image’s ability in dictating the norms of the day cannot be overstated yet, surprisingly enough, western Christians continue to cede aesthetic territories to the nihilistic forces who are dead-set on destroying the remaining structures of differentiation and replace it with their own. We can observe this happening when activists tear down the monuments of old.

How important is the image in keeping the structures of society alive? It is important to start this analysis with an observation of mimesis. What is mimesis? A snake charmer in ancient India (and in some forgotten rural areas of today) demonstrates mimesis when he makes a snake ‘dance’ to the tune of his flute. In reality, however, the snake is barely able to sense the music and is instead fixated on the swaying movements of the flute player. The snake follows the movements of the man playing the flute; it imitates him.

The phenomenon of mimesis runs through much of the natural world and it strongly suggests that any potential imitator is on the lookout for role models. But imitation also, more often than not, inadvertently leads to rivalry.1 This is exactly what makes snake charming a dangerous act; the charmer is, throughout most of the ‘show,’ preemptively fending of the snake’s coming attack. It is quite literally a ‘dance of death.’

The human stare is more likely of leading to a rivalrous relationship as compared to those of beasts. When a person stares into the eyes of another there is a strong likelihood his gaze will be returned in equal measure if not more. The ancient pagan religions knew about this and, therefore, made representations of their deities less human. This is why we see the idols of hybrid human-beast gods.

The native American Coyote, the Indian Hanuman, Kamadhenu, and Ganesha, the Mesopotamian Dagon, the Sumerian Gugalanna, the Egyptian Wepwawet, and the Sphinx are all designed in such a way as to otherize the subject and make it so that they do not fall into the attraction-repulsion of mimesis during admiration. In short, the pagan deities are wary of the inevitable rivalries that come with adoration. Christian iconography, on the other hand, takes an entirely opposite approach to this ‘negative’ mimesis.

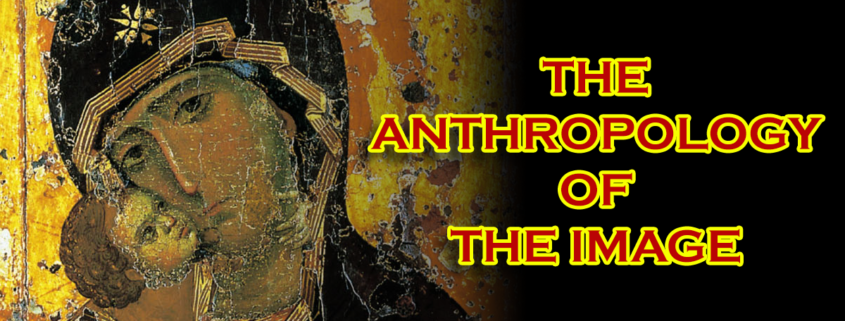

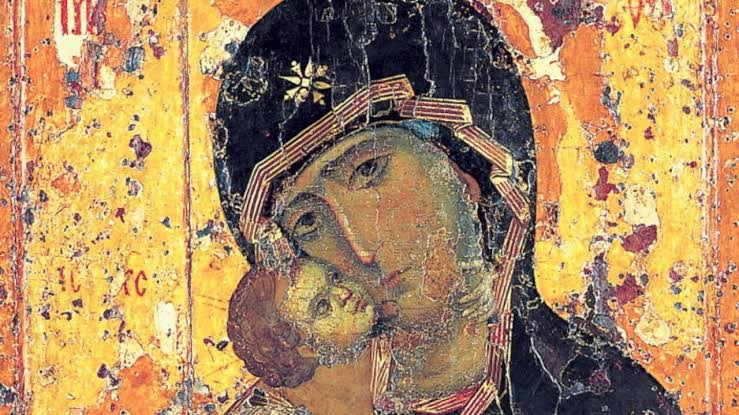

Icons like that of the Theotokos of Vladimir invites the viewer to meet Mary’s penetrating and human gaze. It is rare that a Christian icon will not have this trait which makes the viewer a participant of communion rather than keeping him/her at an arm’s length. Indeed, Christianity, through its iconography, provides us with the revelation that the human face is a treasured part of God’s creation. This is why the existential philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev wrote the following:

The face of man is the summit of the cosmic process, the greatest of its offspring, but it cannot be the offspring of cosmic forces only, it presupposes the action of a spiritual force, which raises it above the sphere of the forces of nature. The face of man is the most amazing thing in the life of the world; another world shines through it. It is the entrance of personality into the world process, with its uniqueness, its singleness, its unrepeatability. Through the face we apprehend, not the bodily life of a man, but the life of his soul.2

It is perhaps because of this revelation that nihilistic forces in the West often target statues honoring their ideological enemies; they cannot stand to see the humanization of their rivals. The nihilistic rioters, themselves masked, and their status quo handlers are not very fond of faces; they seek every opportunity to either caricaturize the countenance of God’s creation or relegate it to the text of their narrative. In this way, they are able to objectify humanity and do with it whatever they please.

Christianity, particularly in its iconography, invites us to look deep into the faces of our neighbors. It boldly challenges us to not fall into the push-pull of mimetic rivalry in our engagement of the human person. This is particularly true in Orthodoxy where icons are made part of the household, therefore encouraging us not to be pulled into the trap of “familiarity breeds contempt,” but rather recognize those nearby as unique and worthy of God’s love.

Christianity also encourages us, through icons, to imitate the holiness as depicted in its images. When we see the icon of the Theotokos of Vladimir, we recognize motherhood as a beloved and treasured role in humanity; this is quite the contrary to modern-day secular icons that consist of movie stars, rock and roll stars, and even fictional characters. Secular icons like that of the rock and roll star provide a model for the imitation of Dionysus–the ancient Greek deity of drunkenness and ritual madness. There is an element of ritual human sacrifice in these secular role models that many overlook.

In our modern-day environment that is filled with images of icons who seek to direct us to their desires, we often overlook the fact that these are fallible individuals who are unable to cover up their scandalous deeds with the glitter and glamour of celebrity. All of us, regardless of creed, venerate images. More often than not, we venerate celebrities and politicians who are unable to cover up their scandals. The subject of Christian iconography, however, testifies to the fact that Christ has redeemed that fallible person in one way or another.

Christian icons each provide us with role models of courage, boldness, patience, intelligence, care, and so on. Everything of this nature rests in Christ being the icon of the invisible God, as declared in Paul’s letter to the Colossians (Col. 1:15). Also, Christ says, “for whatever He does, the Son also does in like manner” (John 5:19). Paul states in his letter to the Corinthian church, “Imitate me, just as I also imitate Christ” (1 Cor. 11:1). As opposed to the chaotic egoism of secular icons, Christian icons always revolve around and seek to inject the element of self-sacrifice into the viewer.

Whereas secular iconography serves as a reminder of humanity’s failure to bridge itself through substitutes, Christian iconography encourages us, through its many subjects of various nationalities, races, cultures, etc., to bind ourselves in a familial manner around the headship of Christ. The image of Christ, whether it be in text or wood, is the window to recapitulation, redemption, and salvation. Certainly, it is a wonderful thing that Christ says: “He who has seen Me has seen the Father” (John 14:9) and “Anyone who loves me will obey my teaching. My Father will love them, and we will come to them and make our home with them” (John 14:23).

-

- René Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning

- Nikolai Berdyaev, Slavery and Freedom

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!