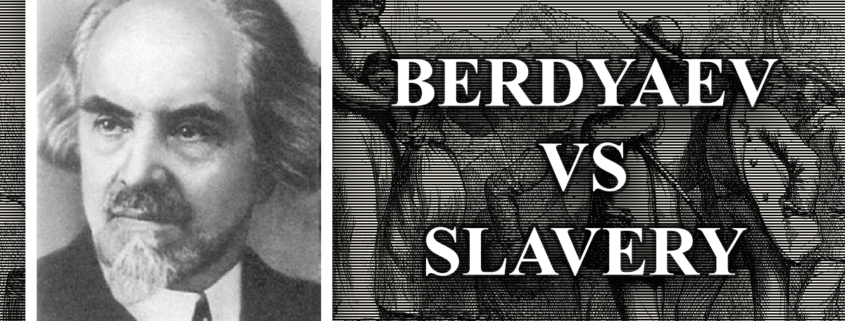

Berdyaev vs Slavery

Man is a riddle in the world, and it may be, the greatest riddle. Man is a riddle not because he is an animal, not because he is a social being, not as a part of nature and society. It is as a person that he is a riddle—just that precisely; it is because he possesses personality.

–Nikolai Berdyaev, Slavery and Freedom

It is not surprising to see that, despite many advances in science, technology, and overall knowledge, humanity is deeply enslaved to both physical and metaphysical idols. The root cause of this, according to Russian existentialist philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev, is connected to the departure from focusing on personality and the entrance into objectivization.

Given Berdyaev’s experience in witnessing and standing against the rise of Communism in early twentieth-century Russia, it must be said that Berdyaev’s literary works deserve our utmost attention, especially as we ourselves witness the emergence of subtler and far more destructive totalitarian systems of our time. It would benefit us to know what made the man whom Solzhenitsyn described as a “brilliant defender of human freedom against ideology.”1

Berdyaev lays the problem of enslavement at the feet of objectivization. What is objectivization? Berdyaev writes that “objectivization is impersonality, the ejection of man into the world of determinism.”2 Berdyaev faults modernity with objectifying almost everything within its sight. The objectification of man causes him to be enslaved to the State, class, mammon, ideology, nature, society, civilization, civilization, culture, and even God.

Let us look at some of Berdyaev’s critiques on the various kinds of slavery that have gripped mankind in the modern age.

On the concept of the State, Berdyaev writes that “the state always repeats the words of Caiaphas; it is the state’s confession of faith.” The words of Caiaphas, of course, are: “It is better for us that one man should die for the people than that the whole nation should perish.” “That which has been considered immoral for a person,” Berdyaev continues, “has been considered entirely moral for the state.”3

On excessive patriotism, Berdyaev says: “National egocentricity, national self-containment, and xenophobia, are in no degree better than personal egocentricity, self-containment and hostility to other people…” Nationalism, Berdyaev writes, “insists upon hatred, it requires hostility towards and contempt for other nations. Nationalism is already potential war.”4

Slavery can be manifest even in Christendom, particularly when we objectify God. “God is not an object to personality,” Berdyaev says, “He is a subject with whom existential relations exist.” It is blindingly obvious that once we objectify God we turn into Dostoevsky’s infamous Grand Inquisitor—one who wants to engineer society through violence into serving God.

In Berdyaev’s critiques, we find a similarity that helps us get to the core of the problem. In every mode of slavery, we see an erasure of personal accountability. We see, with the transformation of persons into things, the rise of utilitarianism. This naturally gives rise to all kinds of exploitation and oppression. Berdyaev writes:

In the cultural and ideal tendencies of our epoch, dehumanization moves in two directions, toward naturalism and toward technicism. Man is subject either to cosmic forces or to technical civilization. It is not enough to say that he subjects himself: he is dissolved and disappears either in cosmic life or else in almighty technics; he takes upon himself the image, either of nature or of the machine. But in either case he loses his own image and is dissolved into his component elements. Man as a whole being, as a creature centered within himself, disappears; he ceases to be a being with a spiritual center, retaining his inner continuity and his unity.5

With the advent of the industrial revolution, we see human persons turning into mechanized units—mere disposable flesh and blood, ready to be exploited by the dominating class. Man turns into a domesticated beast, ready to plow the concrete fields of the modern landscape; his uniqueness and worth all but forgotten. For this reason, Berdyaev initially turned to the doctrine of Marxism.

Witnessing the full onslaught of the Russian revolution and the consolidation of power by the Bolshevik regime, Berdyaev disowned Marxism while, at the same time, clinging on to its criticism of capitalism and the bourgeois spirit. His criticism of Bolshevik totalitarianism led to him being interrogated by the notorious head of the Cheka (the Soviet Secret Police) and one of the architects of the Red Terror, Felix Dzerzhinsky.6 Berdyaev stood his ground and defended personhood in the face of collectivist terror, and won. He was then forced into exile.

Berdyaev’s problem with violent revolutions can be seen in the fact that they are born from the envy of the bourgeois spirit rather than transcending it. “Socialism and communism,” Berdyaev says, “may give effect to a just and equitable distribution of the bourgeois spirit!” Of course, Berdyaev had no desire to perpetuate the bourgeois mentality of pride and aloofness simply because it could not be reconciled with his Christian worldview. He writes:

At one time in Egypt the dignity of immortality was attributed only to the king; all the rest of the people were mortal. In Greece to begin with only gods or demi-gods or heroes and supermen were regarded as immortal; the people were mortal. Christianity alone has recognized all men worthy of immortality, that is to say it makes the idea of immortality absolutely democratic… Christianity has overthrown the principles of Greco-Roman culture, and in so doing has affirmed the dignity of every man, of his sonship to God. It has affirmed the image of God in every man, and Christianity alone is able to unite democracy, the equality of man in the sight of God, with the aristocratic principle of personality, the spiritual equality of persons, which is not dependent upon society and the masses.7

What liberates man from slavery? Berdyaev’s answer is a call to “true aristocracy,” namely one that ascends beyond the impersonal—the herd—and descends to those who are suffering and abandoned. “The principal mark of true aristocracy,” he writes, “is not exaltation but self-sacrifice and magnanimity, which are derived from inward riches, a readiness to descend, inability to feel ressentinment.”8

“True aristocracy,” according to Berdyaev, manifests in creativity, not of the vain kind but towards the betterment of one’s own neighbor. “Great creative men,” Berdyaev writes, “have always thought of themselves as called to service, they have a universal mission.” Not only is creativeness the act of love towards fellow man, but it is also a manifestation of God’s energy in His creation.

Creativeness is liberation from slavery. Man is free when he finds himself in a state of creative activity. Creativeness leads to ecstasy of the moment. The products of creativeness are within time, but the creative act itself lies outside time.9

Indeed, Berdyaev’s answer to theodicy is “anthropodicy,” a justification of man as co-creator in God’s work. This is not far from Jesus’ statement: “Truly, truly, I say to you, he who believes in Me, the works that I do, he will do also; and greater works than these he will do” (John 14:12). The answer to slavery, therefore, is not another political theory but, rather, the recognition that each and every individual is God’s image-bearer. With the voluntary realization of this principle comes true liberation.

1. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Gulag Archipelago, Vol. 3

2. N. Berdyaev, Slavery and Freedom

3. Ibid

4. Ibid

5. N. Berdyaev, The Fate of Man in the Modern World

6. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Gulag Archipelago, Vol. 3

7. N. Berdyaev, Slavery and Freedom

8. Ibid

9. Ibid

Thanks for the quote on creativeness. It comforted me.

When I’ll be asked in heavens how did I love (others) during my life, I’ll be at least in position to answer “through creativeness” 😉

I think I’m on a mission.

But I still have all the publishing work to be done!

Everything is as if I don’t know what is time.

I guess I should 😉

Glad you found it insightful 🙂