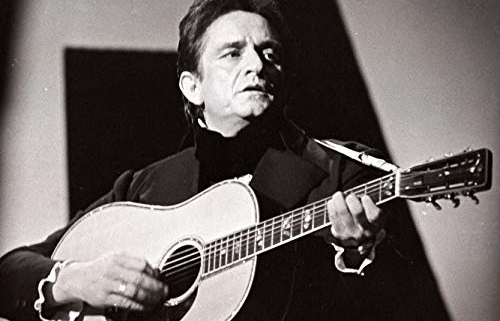

The ‘Man in Black’ vs. the State’s Sacred Violence

This classic essay originally appeared on WND.com in December 2016.

As poets are wont to do, Johnny Cash led a prophet’s life for his time. His performance art and accompanying dusty, rumbling lyrics dared to look into the soul of America’s violence-haunted heart with equal parts affection and anger.

When I speak of the state’s “sacred violence” I mean it in an ironic way. In the old pagan days, only the high priests reserved the right to sacrifice an innocent human life to appease the gods for the protection of the masses. Today, governments continue that bloody tradition every time they maintain a monopoly privilege to initiate physical aggression against nonviolent persons to stave off the god of demos, or the Crowd, and its chaotic wrath.

Since the state acts as the nexus of sacred violence to control, stave off and increasingly foment mirror violence and strife in our culture, Cash used his platform to challenge its mechanisms in some of his most powerful ballads. From the song “Man in Black”:

And, I wear it for the thousands who have died,

Believin’ that the Lord was on their side,

I wear it for another hundred thousand who have died,

Believin’ that we all were on their side.

In these four lines, Cash prophetically deconstructs the entire essence of the state’s power. The state’s life is in the blood it sacrifices for its unity, supremacy and continuity. The state, to maintain its oneness, must unify the populace around a common cause – in essence, it must always create or amplify a stress that must be eaten by or expunged from a community to keep the transcendent ecstasy of temporary peace.

Think of the state’s way of culture, as any agency that misses the mark of love, as a shortcut to heaven that leads to hell. The heaven it promises is peace, that feeling of relaxation in our bones we feel when strife ceases between our neighbors and we find common being in solidarity with a shared task of great importance. You know, like war. That’s where the shortcut in the woods to heaven brings us to hell.

“War is the health of the state,” Randolf Bourne said. Indeed, without it or the ever-looming rumor of it, the state would cease to exist. It’s why people mark time by it with holy days: We feel a sense of transcendence in remembering the awesome unity and triumph war provides otherwise rivalistic neighbors.

The role of singer-poet-prophets like Cash is to charm our neighborhoods with rhythmic patterns and melodic beauty so as to disarm us so we can receive hard truths we wouldn’t otherwise face. A spoon full of musical sugar makes the apocalyptic medicine go down.

Cash elucidates a Christian truth about the state that goes back to the prophets of old Jerusalem, themselves men who wore black so to speak in protest of their nation’s abuses of human life. Since time immemorial, the state’s leaders have used a tribe’s gods as banners to incite the need to sacrifice human bodies for war. The territory and spoils were always handled back stage, for the pragmatic priestly caste. But the pageantry of war has always been associated with gods’ will. Indeed, what else but a god could inspire such otherworldly courage men must summon to throw their bodies into a field of meat-grinding and agony at the mere mention of a foreign monster prowling from afar.

“Man in Black” shows us that thousands die “believing that the Lord was on their side.” What Lord? Cash sang this song in the shadow of the Vietnam War, an event that sacrificed close to 60,000 lives and millions more family members with generational scars from the tortures of war. It certainly wasn’t Jesus who desired these human sacrifices. He was on their side in the sense that he mourned those who, like himself, are victimized by a maddened crowd desiring sacrifice. To them Jesus said, “Go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice.'” Have we, 2016 years later, even begun to learn what this means? It certainly means the “Lord” Jesus quotes had no desire to see 60,000 human lives sacrificed, especially over an evil lie like the Gulf of Tonkin incident proved to be.

So what Lord would want this mass sacrifice? The answer lies in the lyrical mirror that follows the verse: “another hundred thousand who have died … believin’ that we all were on their side.”

The “Lord” is not God but rather our false god we call the nation-state. “We all” are the false “Lord” that led these thousands to sacrifice their lives for a grand lie of strife and and avarice. God forgives us of this grave evil because we don’t know what we’re doing. But we should. We should have the courage to face our nation’s false transcendence-creating sacrificial machine built on unnecessary violence and forgive ourselves.

Jesus said “Father, forgive them, for they know not what we do.” The imitation of Jesus frees us to forgive ourselves so that we can be unshackled by the shame that causes us to stumble into fits of mass violence again. From this place of humility we can then resolve never to participate in the false transcendence of collective violence again, no matter how heart-struck or fear-struck we may be by crooked state-priests calling for war. As another prophet, the Apostle Paul, said to his fellow Romans enthralled by blood sacrifice to appease national gods, “In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent.”

Cash, as a lover of Jesus who sang about the prophets and wrote a book on the life of Paul, felt this command deep in his soul. So he sang it to us his whole life. ‘Til his dying breath. He was tortured by the cognitive dissonance the pull of our personal hallucinatory desires for power and satisfaction at other’s expense creates; the same crowds that adored him as an idol also sacrificed thousands unto the “Lord,” the nation, and its need for victims to perpetuate mass incarceration and war rituals.

That’s why Cash wore a coat of mourning “for the prisoner who has long paid for his crime / But is there because he’s a victim of the times.” Because the Gospel of Jesus destroyed the false sacred unity the sacrifices we make to the gods of our image, Cash’s conscience was pricked. And so ours continue to be as well, though we labor to deafen our ears “with cars and fancy clothes.”

Forty-five years since the “Man in Black” was first sung, our television tells us every day we have more overseas monsters to fear, poke and sacrifice our children to defeat. Forty-five years later, millions of nonviolent prisoners remain victims of the times. How long shall we wait to create a new time? A time where we snap out of the stupor of groupthink and realize that the state’s sacred charms no longer work and have always been rooted in lies?

Until then, pardon me if every now and then, I’m the man in black.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!